‘It could not be denied that the instruction received by artisans in our factories was at least equal, if not superior, to the factories of any other nation. Meanwhile, [technical] schools were established on the continent while there were in this country no technical schools.’

- Sir Bernhard Samuelson, Member of Parliament for Banbury, 1868.

Throughout most of the 19th century the British Empire was the world’s foremost power. Britain had maintained a large navy which allowed her to control many of the world’s waterways and trade routes, however, France, now under the rule of Napoleon, was the dominant power on mainland Europe.

During the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815), the Royal and Merchant Navies formed convoys instrumental in the uninterrupted trade and transportation of goods. Simultaneously, the Royal Navy blockaded French and French allies’ ports, which kept France locked to the continent, thereby limiting troop movements around the coast.[1] Britain had consistently utilised the diplomatic strategy of aligning itself with the second or third strongest power in Europe to maintain pressure on France. This, combined with dominance in international trade, meant Britain was able to come through the wars relatively unscathed, and arguably more powerful, when compared to other nations.

Victory over Napoleon brought a period of relative peace throughout Europe. Britain, with its fast-industrialising economy and Royal Navy able to control a vast colonial network virtually unopposed, could now focus on its global ambitions.

During the 17th to 19th centuries Britain had been at the forefront of an agricultural revolution that was sweeping across Europe. The British Agricultural Revolution led to an unprecedented increase in population. This population increase, combined with significant increases in productivity, meant there was a large urban workforce available, potentially being a direct cause of the First Industrial Revolution.

During the late 18th and 19th centuries Britain was by far the dominant industrial power although, by the mid to late 19th century and the emergence of the Technological Revolution, countries such as Germany and the United States of America were becoming increasingly industrialised and threatened to rival Britain’s dominance. In the 1880s the United Kingdom’s share of global manufacturing output was 41%, by 1913 this had dropped to just 30%.[2]

There are many theories that explore the cause of the United Kingdom’s decline in manufacturing output and the rise of nations such as Germany and the United States of America. One theory is the Long Depression (1873-1896), during which there was large-scale deflation and significant global slowdowns in manufacturing. The depression hit Britain most severely allowing other nations’ industrial output to catch up. Towards the end of the Long Depression the United Kingdom’s focus began to shift towards the service sector. This was at the expense of the industrial sector in which employment grew by 2% at the end of the 19th century compared to 9% in the service sector.[3]

There were some members of British business and government that believed there was an additional reason for Britain’s decline versus other industrialised nations. They believed that the United Kingdom was falling behind in education, specifically technical education. When we compare the number of university students in the United Kingdom to that of Germany in 1913, we find that while the United Kingdom had approximately 9,000 students in university, Germany had 60,000 - a significant gap that Britain would need to close.[2]

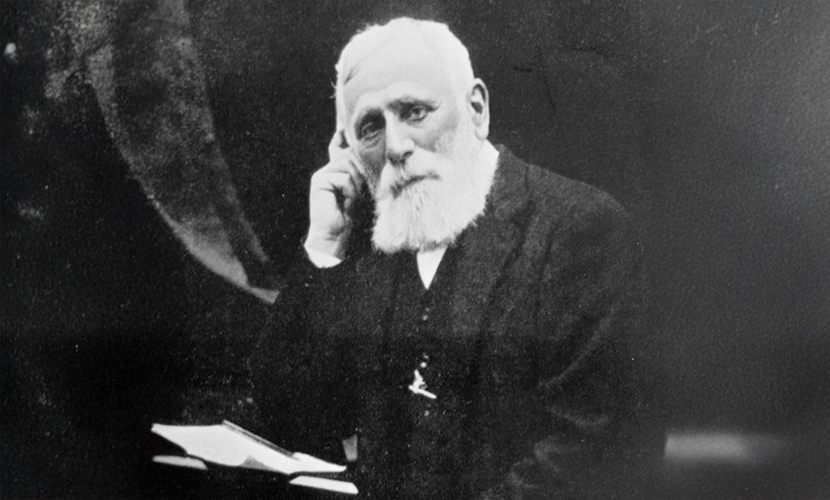

Sir Bernhard Samuelson, 1st Baronet, P.C., F.R.S., was an industrialist and early advocate for technical education in the United Kingdom. In 1859 he was elected to be a Member of Parliament for Banbury, Oxfordshire before being defeated later that same year in the general election. In 1865 he was elected once again in Banbury and maintained that position until 1895.

In March 1868 Samuelson addressed the House of Commons with a motion for a select committee:

‘Now, it could not be denied that the instruction received by artisans in our factories was at least equal, if not superior, to the instruction received in the factories of any other nation in the world. Meanwhile, schools were established on the continent for conveying, not only theoretical instruction, but also for the purpose of imparting instruction in practical manipulation. There were in this country no technical schools.’

He continued to provide examples of the formation of colleges in France and polytechnic schools in Germany and that the United States of America had voted towards a land value of no less than $8 million for technical schools. Samuelson believed that ‘encouragement of technical instruction in this country would not merely promote arts and manufactures, but would tend to the advancement of the general education of the people’.[4]

The motion passed and in 1868 Samuelson chaired the House of Commons’ Select Committee on Scientific Instruction. The Committee made fifteen key points including expanding scientific instruction for every child to benefit the working class, all children not obliged to leave school before the age of fourteen should be taught science, and fees alone cannot adequately fund colleges of science and schools of scientific education; other establishments, whether national and local government or other benefactors could contribute.

Bernhard Samuelson was a successful politician, businessman and educationalist. He was a member of the Institution of Civil Engineers and the Institute of Mechanical Engineers, won a Telford Medal in 1871 and was made a fellow of the Royal Society in 1881. In 1884 he formed a technical institute in Banbury. However, it was the 1868 Committee that would be his greatest legacy as it helped lead the way for future reforms in scientific and technical education.

In 1889 the Technical Instruction Act was published and specifically highlighted the need for national technical education to ‘halt industrial and manufacturing decline’ in the United Kingdom.[2] This sounded like the right direction but the fact remained that between the 1860s and 1890s technical education was being defined as ‘instruction in the principles of science and art applicable to industries’ as stated in the 1889 Act, and ignored ‘teaching the practice of any trade or industry or employment’.[5]

In 1888 the Local Government Act had created new county borough councils. These local authorities were given greater powers as part of the Technical Instruction Act. They were now allowed to ‘supply or aid the supply of technical instruction’. This could be achieved through powers that allowed the borrowing of money. These powers were limited and, in the end, did little to advance its cause - local authorities were only allowed to spend up to one penny in every pound towards technical education. This lack of funding combined with ignoring the teaching of trade and industry-related skills meant the Technical Instruction Act was far off what was required to reverse or even slow the manufacturing decline. However, the publishing of the Act did mean progress was being made, albeit slowly, and awareness of the decline of technical instruction was becoming greater.

In 1890 an act of parliament, seemingly unrelated to education, was established. The Local Taxation (Customs and Excise) Act passed legislation to decrease the number of public houses by introducing an increased tax on alcohol in an attempt to reduce consumption. Originally the money raised was to go towards compensating the publicans who were forced to close their doors. However, some members of parliament objected. This left the Government in an unusual position of having a yearly tax stream with nothing to spend it on. The tax soon became known as ‘whiskey money’ and, in July 1890, Chancellor of the Exchequer G. J. Goschen announced that the money would go towards funding for technical education.[2]

Although whiskey money was a varying tax stream dependent on the number of drinks consumed each year, it was no minor income. In the financial year ending 1891, £740,376 was paid to English and Welsh authorities, and at no time during the same decade did the money drop below that level. In fact, the money tended to increase. In the year 1900, English and Welsh authorities had £1,028,001 paid to them. Whiskey money was so successful that it outstripped funding from the Department of Science and Art and led to increased provision of evening classes in technical education and the expansion of facilities in local regions. Money from the tax was not only spent on technical education, but also on museums and the Geological Survey. It can be inferred that without this money ‘most of the work of the Technical Instruction Committees would have been impossible’.[6]

The Technical Education Act of 1889, although not wide enough in scope to slow the decline of manufacturing in the United Kingdom, worked well with the Local Taxation (Customs and Excise) Act of 1890. The 1889 Act by itself did not provide enough autonomy in funding for local councils and, as such, many did not make use of the powers provided. It had however, in combination with the Local Taxation (Customs and Excise) Act, kick-started a revolution in education.

Prior to 1889 there were very few schools or colleges specialised in technical education in Essex. The powers afforded to the local council through the introduction of the Technical Instruction Act allowed the county to introduce the penny rate to better provide education of a technical nature which was then enhanced further by the additional whiskey money grants provided by the Local Taxation (Customs and Excise) Act.

In the first year of receiving whiskey money, Essex County was granted about £22,000. Despite the increase of grants nationally over the first decade, for Essex, this gradually diminished year on year. In 1891, to help regulate the penny rate and whiskey money funds, a Technical Instruction Committee of thirty-five members was formed in Essex.[7]

A major shift in education funding came with the Education Act of 1902. The Act introduced a Higher Education Levy which was to help fund the increasing costs of higher education, including technical education. The 1902 Act, which upon introduction annulled the Technical Instruction Act of 1889, was instrumental in modernising the school system in England and Wales. The Act led to the abolishment of school boards and brought schools under the control of Local Education Authorities.[8] These Local Education Authorities had the power to create new secondary and technical schools however, as before, the technical schools were primarily based in pure science and the arts, not in the practical application of skills. Practical technical education only became more prevalent because of World War 1 when it was deemed sensible that young people should be taught skills that would more greatly prepare them for employment.

The 1902 Act was highly controversial at the time and eventually led to a landslide victory for the Liberals over the Conservative Party in the 1906 general election. However, it appears to have been a long-term success; by 1914 over one thousand secondary schools had been created under the Act, 349 of them for girls. From 1913, junior technical schools were built to provide skills needed in local industries. Importantly, the Act allowed Britain to develop a system of university education more closely resembling that within Europe.[9]

The Essex Technical Instruction Committee appears to have been one of the most active across the country. One of the first grants awarded was to the Central Laboratories at Chelmsford, which later became the East Anglian Institute of Agriculture, then Writtle University College. Vocational classes, managed by local technical instruction committees were also established across sixty parishes. These were granted between £5 and £500 a year.

Two of the largest projects that were undertaken by the Committee during the late 19th century were the science schools established at Walthamstow and Leyton in 1897 and 1898 respectively. These schools were later developed into technical colleges and were eventually replaced by the South-West Essex Technical College and School of Art.

The two science schools in Walthamstow and Leyton were so successful that by about 1910 a local demand arose for the provision of technical day schools. The development of these was initially delayed owing to the start of World War 1, but it was not long until the first opened at Walthamstow in 1917 with a provision for 75 pupils and an equivalent school at Leyton opened in 1918 with 100 pupils. Walthamstow also saw the opening of a Commercial School for Girls.[10]

It appears that although national legislation was slow to adapt and adopt technical education, the public embraced it, which in turn led to increased further and higher education reform. In 1924 the demand for technical education in the Essex region had become so strong that the District Sub-committees officially recommended the construction of large technical colleges across Essex.

References

R. Knight, Convoys: The British Struggle Against Napoleonic Europe and America, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2022.

Richard, “A Short History of Technical Education,” 2009. [Online]. Available: https://technicaleducationmatters.org/series/a-short-history-of-technical-education/. [Accessed 21 February 2021].

J. Baten, A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present., Cambridge University Press, 2016, p. 58f.

House of Commons, Motion For A Select Committee [Hansard], vol. 191, London, 1868.

UK Parliament, Technical Instruction Act 1889, London: HMSO, 1889, pp. 384-388, c.76.

P. R. Sharp, “’Whiskey Money’ and the Development of Technical and Secondary Education in the 1890s”, Journal of Educational Administration and History, vol. 4, no. 1, p. 31, 1971.

Essex Education Committee, Opening Ceremony of the South-West Essex Technical College and School of Art, Silver End, Witham, Essex: E. T. Heron & Co. Ltd, 1939.

UK Parliament, Education Act 1902, London: HMSO, 1902, pp. 126-145 c.42.

G. R. Searle, A New England?: Peace and War 1886-1918, Oxford University Press, 2004, pp. 333-334.

W. R. Bray, The Country Should be Grateful - The War-time History of the South-West Essex Technical College and School of Art, London: The Walthamstow Press Ltd, 1947.

Researched and written by Thomas Barden