‘It was commonplace to find that out of 120 Motor Vehicle Mechanics [due to arrive for training], 60 would turn into Welders the day before their expected arrival, while of the other 60, 45 would turn out to be Electricians.’

- W. R. Bray, ‘The Country Should be Grateful’, 1947.

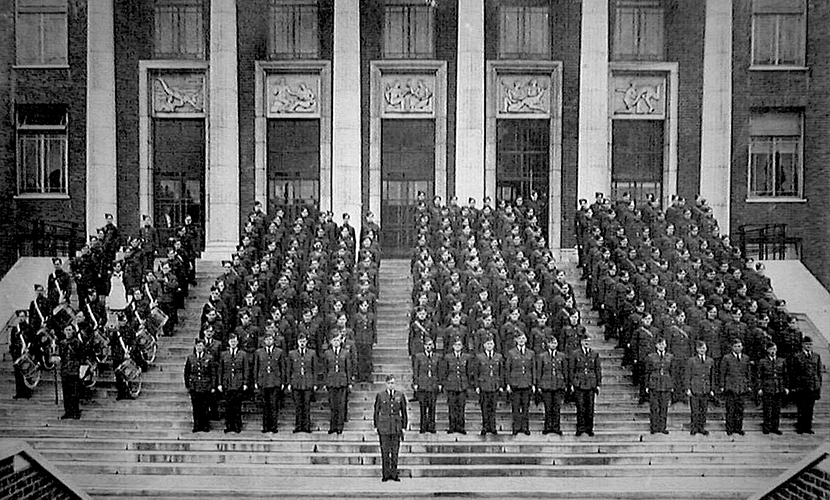

The end of 1939 and beginning of 1940 saw the Principal and Governors work tirelessly through intense negotiations with local and national government departments. The September negotiations were ultimately successful and the College was allowed to maintain civilian education provided it would train men and women from the military. The second round of negotiations was with the military itself. Decisions were made regarding the courses the College could provide taking into consideration staff, equipment and facilities. An agreement was reached and on 11th January 1940 just over one hundred British Army soldiers entered the College to begin training. These were the first of ‘over 12,000 service trainees to pass through the College, a number which is claimed as a record unbeaten by any similar institution in the country.’[1]

The College’s facilities had already been stretched during the first year of opening. Now, not only were the military going to be training at the College alongside civilians, but they were also to be provided accommodation. Many classrooms and staffrooms in the basement (now the ground floor) were reserved as living quarters with the rest used for classes.

Although the army was the first branch of the military to arrive at the College it was originally planned to be the Royal Air Force (RAF) arriving in October 1939. The principal had provided a summary of facilities available and a list of equipment the College would need to provide effective training of RAF troops. However, it was decided that due to ‘the absence of heavy casualties and the low rate of destruction of machines…many of the projected training schemes of the Air Ministry [were] either redundant or unnecessary, and among these are the plans for Walthamstow and Dagenham [college’s].’[1]

In hindsight this appears to have been an error on the part of the Air Ministry as a year later the UK would be subjected to the Blitz and would require as many aircraft as it could possibly field. RAF troops finally started to arrive by the end of 1940 to begin their training in radio mechanics, engine maintenance and air-frame maintenance.[2]

The number of servicemen and women was increasing at an unsustainable rate. The College could no longer provide accommodation as it needed the extra classroom space to effectively train military personnel. To solve the problem space was found at the recently evacuated Sir George Monoux Grammar School. The school’s equipment had already been requisitioned by the College rendering it temporarily mothballed. On the troops’ first night in their new accommodation an unfortunate incident took place when a parachute mine dropped close by. Although it wasn’t a direct hit, damage was done to the building’s roof and windows. Thankfully there were no casualties and the men ‘set to with a will to repair the school as far as possible.’[1]

Logistics during the war years were certainly difficult. The College had to move quickly to make changes to staffing and facilities at very short notice:

‘It was commonplace to find that out of 120 Motor Vehicle Mechanics [due to arrive for training], 60 would turn into Welders the day before their expected arrival, while of the other 60, 45 would turn out to be Electricians.’

This meant staff often went through courses themselves so they could be adaptable and train any number of disciplines they were not specialised in. As a result, many staff found themselves with a far wider experience of trades at the end of the war than they had going in.[1]

The arrival of the RAF brought with it a whole new set of equipment and staffing problems. Equipment was in short supply and almost non-existent, while extra staff were brought in from other departments and local secondary schools. Thankfully, the Government set up a supplies department at South Kensington so the College could access a steady supply of various components and equipment, including cathode ray oscilloscopes, meters and raw material for soldering and brazing.

Towards the end of 1942 the RAF was running low on recruits that had the required education standard. To solve this problem the College established a set of courses called Preliminary Air-Crew Training Courses and included subjects such as English, maths, physics, geography, technical drawing, modern history and current affairs. Overall, 350 men went through these courses split into ‘flights’ of 25. Continued lack of space meant The Salvation Army Hall in Hoe Street was used for many of these classes.[1]

Alongside the male branches of the military were the female. Over the course of the war members from the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS), Women’s Auxiliary Air force (WAAF) and Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS) would attend the College for training in a broad range of subjects.

The first branch to arrive was the ATS. In 1941 training in typewriting, arithmetic and English was provided by the Commerce Department.[2] This provision continued to expand and went on to include general knowledge, army administration and organisation. Over a four-year period 500 women and 150 men were trained in these classes. In 1942 members of the ATS began to train as welders and instrument mechanics.[1]

The military soon found itself needing for a greater number of trained cooks. In 1941, under the direction of Mrs L. A. Brazier, Head of Department for Domestic Science, a steady stream of WAAF members took intensive five-week cookery courses at the College. These courses were designed to train cooks under all circumstances from properly equipped kitchens to emergency field kitchens. Nearly 300 members of the WAAF were trained on these courses.[1]

The last branches of the military to arrive at the College were the Royal Navy and Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS). Upon their arrival the College was designated as HMS Shrapnel (a designation shared between several land-based Royal Navy facilities) and a plaque commemorating this can be seen at the top of the College main steps. Notably, the Royal Navy was the only branch of the military that continued to use the College for training after World War 2. They left in 1947 although originally planned to stay longer.

The first members of the Royal Navy to arrive were part of the Fleet Air Arm. As a result, the training provided was replicated from the RAF classes. This certainly made a third branch of the military arriving at the College easier to manage. As time went on the Royal Navy had a need for radar to be fitted to ships thereby requiring a great number of trained maintenance workers.[1]

It should be noted that of the three main branches of the military that attended the College the Royal Navy was the only branch that treated their men and women with complete equality; men and women attended the same courses in mixed gender classes and took part in the same examinations. The only difference was the selection of recruits: members of the WRNS were selected based on previous academic accomplishments, whereas the sailors had to take two entry tests.[1]

The importance of the College’s role in training the Royal Navy and WRNS recruits is highlighted by Mr W. R. Bray when he writes about the arrival of Headmaster-Lieutenant L. C. Toms, B.Sc., R.N. (served on the North Russia Convoy Runs) to the College, ‘[His arrival] shows the importance [of the courses] in the estimation of the Naval authorities.’

Just like civilian education training the military didn’t end at the College gates. Many teaching staff were dispatched to searchlight stations, gun sites and RAF stations. In the 1940-1941 academic year over 300 lectures of this nature were given.[3] These off-site training schemes were adjusted and increased significantly during the 1942-1943 academic year with whole courses, as opposed to individual lectures, being delivered to servicemen. These staff ‘travelled the countryside by day and night, in summer and winter, in bright sunlight and in the darkest black-out. At times the lectures were rudely interrupted by the call to Action Stations.’ Several members of staff arrived at gun sites that had been deserted and then had to make the long journey back to the College.[1]

Towards the end of the war a series of rehabilitation courses were set up for men and women who had served so they could better transition back to civilian life. There was a great demand from the women of the ATS and WAAF for childcare and domestic subjects alongside courses involving glove and slipper making, the art of wearing clothes, correct use of makeup and furnishing, whereas, for the men, the Engineering Department provided a large range of workshop courses.[4]

References

W. R. Bray, The Country Should be Grateful - The War-time History of the South-West Essex Technical College and School of Art, London: The Walthamstow Press Ltd, 1947.

Waltham Forest College, Fiftieth Anniversary: Waltham Forest College, London, 1988.

H. Lowery, “South-West Essex Technical College and School of Art Annual Report Session 1940-41,” The Guardian Press, London, 1941.

H. Lowery, “South-West Essex Technical College and School of Art Annual Report Session 1944-45,” The Guardian Press, London, 1945.

Researched and written by Thomas Barden