‘We were there when the 1944 Education Act was coming into force....The talk was of the fresh traditions to be created: the secondary moderns were to produce new citizens for a new age.’

- Mr Robert Barltrop, ex-student of Forest Training College, 1988.

World War 2 hostilities ended in 1945, first in Europe with the surrendering of Germany on 8th May and finally with the formal surrender of Japan on 2nd September. After six years of war the South-West Essex Technical College would once again have to find its place in a changing Britain.

The first major change within the College was the wind down of military training as the country transitioned from a wartime to a peacetime economy. Both the Army and the Royal Air Force (RAF) enacted a significant wind down of training at the College upon the cessation of hostilities, although staff were still called out to provide lectures at local gun emplacements and camps and some evening classes continued. By contrast, the Royal Navy continued to train in the College up until 1947.[1]

Much of the training that was formerly designed for the military was now transitioning into training and rehabilitation for ex-servicemen and women to assist with the transition back into civilian life. These courses were run under the Further Education and Training Scheme of the Ministry of Labour.[2]

There was also a wind down of wartime factories which were to be replaced by existing and emerging industries. This would require the civilian workforce to receive a degree of retraining. As such, the years immediately after the war were not much quieter than those during as indicated by Principal Lowery in the 1945-1946 Annual Report:

‘Though this is the first complete year since the cessation of hostilities, it cannot be said that there has been any real return to normal conditions, as Radio Courses for Naval Personnel continued undiminished throughout the year and we were asked to provide in addition large numbers of special courses for ex-Service men….Lack of accommodation has been the key to most of our major problems during the year.’[2]

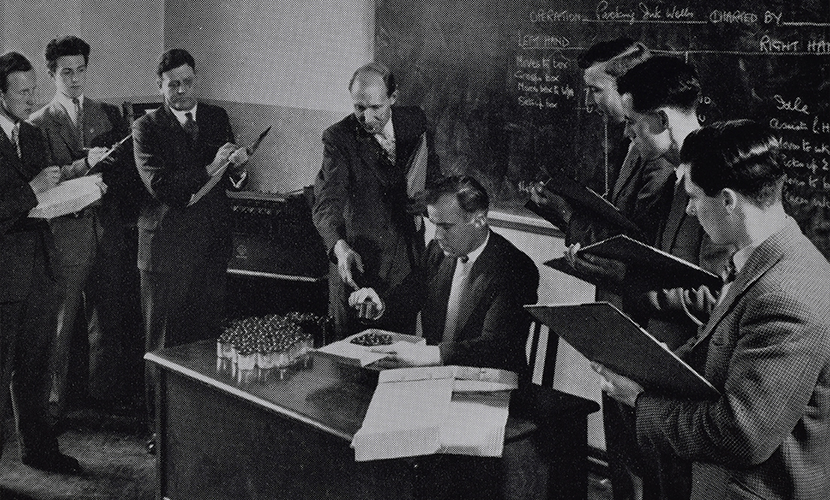

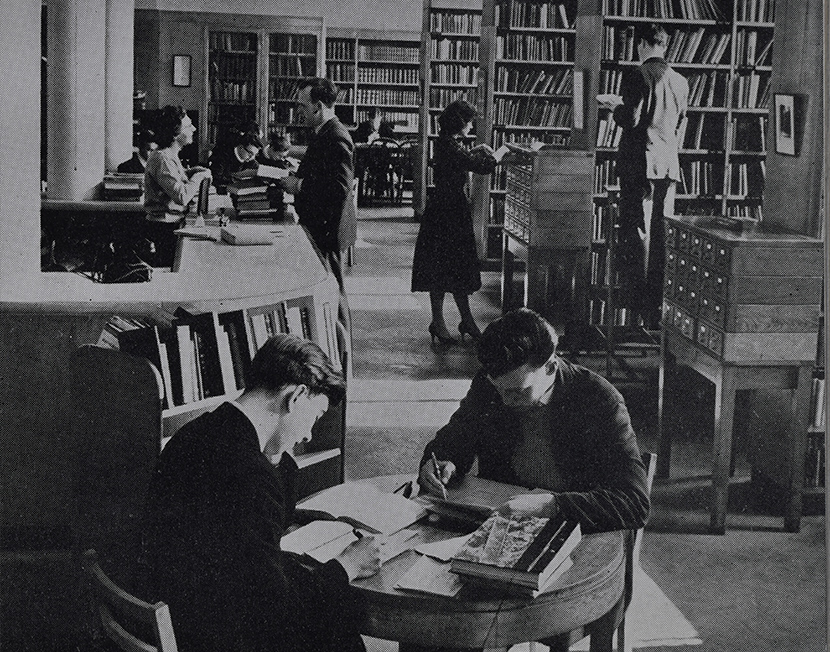

At this same time a major shift was happening in the education sector with the introduction of the 1944 Education Act, also known as the ‘Children’s Charter’, which more greatly recognised technical education provision for children who would benefit from learning a trade. In 1945 the Crown Film Unit produced a film called ‘Children’s Charter’ to promote the Act. The film features clips of the College’s workshops, classrooms, library and swimming pool.[3]

The Children’s Charter aimed to reform education across the country and to make right the lack of good quality schools due to bomb damage and a lack of construction of new schools during the war. Some key actions were to lengthen the school life for all children, decrease the size of classes, introduce a system of compulsory part-time education up to 18 years of age, provide adequate technical and adult education facilities, and expand youth services and teacher training. The most important of these reforms was the expansion of teacher training as there was a limitation in the number of facilities across the country able to do so; the existing facilities could be expanded but not to the extent that was required. The government also feared a reduction of teachers due to the casualties of war and so an emergency training scheme was established which would mostly draw trainees from the older age groups.[4]

In November 1945 the South-West Essex Technical College became home to the Forest Training College under the stewardship of Dr A. Plummer, formerly Head of the College’s Commerce Department.[2] The Training College had a capacity for 130 students resulting in people waiting for a place on the course. Those who waited would often take positions as temporary unqualified assistants in schools.[5]

Mr Robert Barltrop, ex-student of Forest Training College, sums up the ethos of the training schemes:

‘A certain educational modishness ran through the course. We were there when the 1944 Education Act was coming into force, and the majority of us were going to teach in the newly-established secondary modern schools. The talk was of the fresh traditions to be created: the secondary moderns were to produce new citizens for a new age. And we, in turn, had to be well adjusted and with it persons fitted to the guides in that regime. In fact, I think the Emergency Training Courses did produce a high proportion of teachers with a strong sense of vocation. But in ten years the new age went sour; by the late 1950s the 1944 Act’s tripartite system was being attacked widely, and the move towards replacing it with comprehensive schools was underway.’[5]

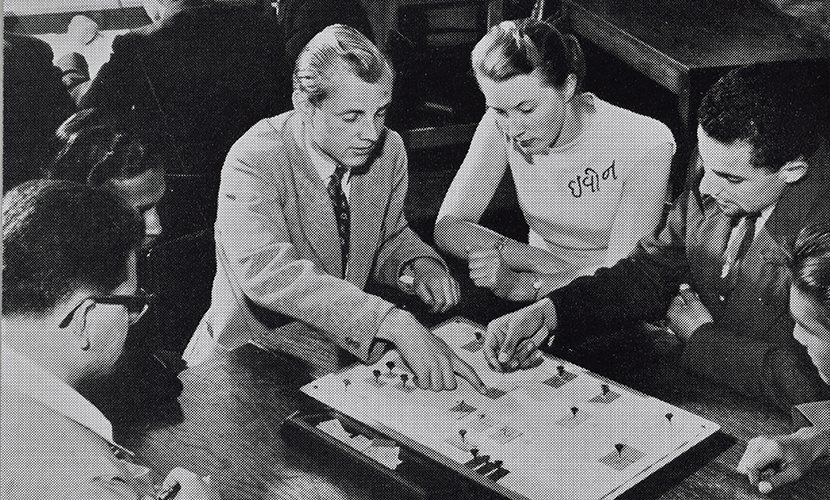

The Forest Training College had an active social and enrichment programme helped by an eager Students’ Union Committee who organised various functions. One notable moment was ‘on the day of the Children’s Christmas Party, when the lift broke down, and a particular “Thank You” is due to the gallants who toiled up and down the endless stairs from the refectory with trays of food.’[6]

The Training College also had its own cricket team and football team. The cricket team appears to have not been very successful, ‘Running between the wickets and fielding must improve if more success is desired.’ However, much humour was had at the Staff v. Students match, although this was somewhat overshadowed by one of the players needing a hospital visit.[7]

The football team started out ‘with great enthusiasm’ and the ability to field two teams, although they ended the season barely able to field one. In the 1949-1950 season fourteen games were cancelled either from the College team not being able to field eleven men or the grounds being unfit. At the end of the season, twenty-two games were played with nine wins, four draws and nine losses, with 61 goals for and 70 against. It is to be noted that all but two of the College’s games were played away due to not having a pitch available on Saturdays.[8]

The Forest Training College’s final year was 1949-1950. By this time emergency training schemes across the country had trained many thousands of new teachers and Forest College had played its part. In the 1948-1949 academic year the College ended the year with 127 students and in 1949-1950, the final year, the College ended with 133. Sidney Rees, Editor of the June 1950 issue of the Forest Training College Magazine, stated in his opening address that ‘when the Autumn term commences [after Forest Training School has closed], there will be some five hundred of us drifting into staff-rooms, all over the country, who once drifted into Room 12.’[9]

During the war years the South-West Essex Technical College continued to have social and cultural events and clubs. The main outlet was in the form of theatre shows and performances often by the military themselves. The College Amateur Operatic Society (CAOS), initially formed in 1938, unofficially broke apart for a period during the war as full-scale productions were halted.[10] However, after the war, things could start getting back to normal and the College was able to become a cultural hub of music, performance, exhibition and festivities for students, staff and the wider public.

The CAOS was able to reform after the war and had many new members join. Mr Coxif, the original music director, and a few of the founding members also re-joined and in 1947 the first post-war show, Rebel Maid, was performed. In total The CAOS put on no fewer than 21 performances during the period of 1947-1959.[10]

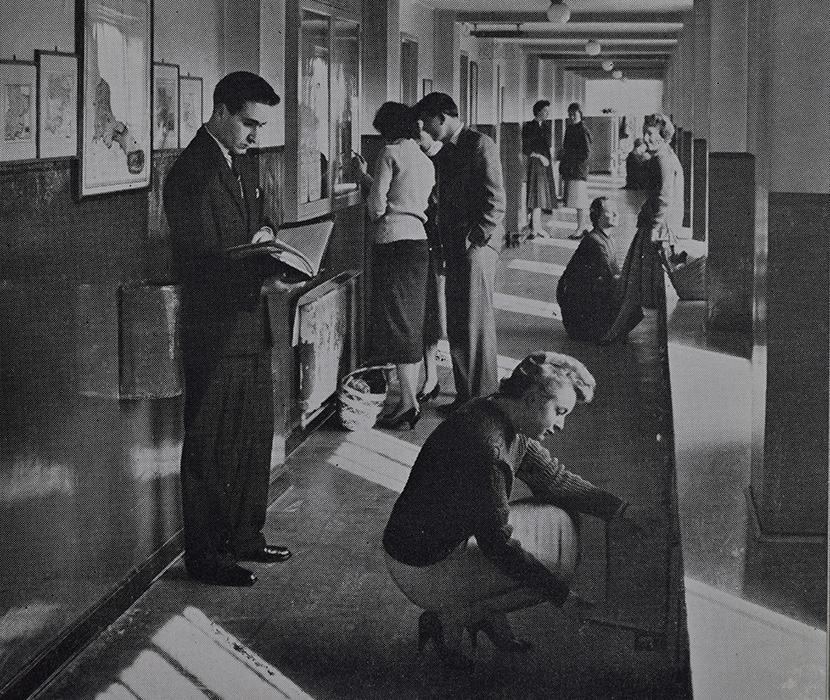

The CAOS wasn’t the only theatrical element to the College. In 1950 drama classes were established and led to quite a considerable pool of talent. The main purpose of the classes was to ‘concentrate on theatrical study and research’. Although public performances were shown it was only when they would actively contribute to the training of members.

Principal Lowery declared in his 1953-1954 Annual Report that ‘the College offers a dramatic training which few similar institutions can rival.’ This bold claim can be backed up by the work put into providing high-quality facilities for students. A practice theatre was established in the Social Studies Department and equipped with portable lighting, flexible staging, recording equipment and a new curtain. Dr Lowery acknowledges these facilities in the report by saying they are ‘comparable with those of the larger professional training schools.’[11]

Students from the drama class made the local press and a mention in The Times Educational Supplement when they staged a six-night public showing of ‘The Drunkard, or The Fallen Saved’ an American temperance play from 1844. The show was packed full each night and gained the accolade of being the longest running show in the College’s history up to that point.

Many students passed drama teaching examinations at the College with one student moving on to qualify at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama. Others attended the Central School of Speech and Drama and the College was represented by two students at the London School of Dramatic Art. In the 1953-1954 session Miss Jean Ratnage, Miss Margaret Cutter and Mr David Darling were invited to join a German Ministry of Education sponsored theatrical company tour of German educational institutions in Hessen. They were there for four weeks and gave a total of thirty performances.[11]

Between December 1953 and January 1954, the College hosted the Annual Festival of the National Union of Students, the first occasion the festival had been held in a technical college.[12] The festival had over 500 delegates from colleges and universities both at home and overseas. The finals of the Debating Competition were also televised by the BBC. There were several guest speakers including Spanish diplomat, writer and historian Salvador de Madariaga; British journalist and satirist Malcolm Muggeridge; and British politician Christopher Mayhew, alongside musical recitals, visual arts exhibitions, sports competitions and an exhibition of books.[11]

In 1959 the College campus expanded to include a building now known as the Lowery Building. The building opened to coincide with the 21st anniversary of the College. It cost £100,000 and was mainly used for architectural and building students.[5]

References

British Red Cross, “The beginning of the Red Cross,” [Online]. Available: https://www.redcross.org.uk/about-us/our-history/the-beginning-of-the-red-cross. [Accessed 28 December 2020].

H. Lowery, “South-West Essex Technical College and School of Art Annual Report Session 1940-41,” The Guardian Press, London, 1941.

W. R. Bray, The Country Should be Grateful - The War-time History of the South-West Essex Technical College and School of Art, London: The Walthamstow Press Ltd, 1947.

H. Lowery, “South-West Essex Technical College and School of Art Annual Report Session 1944-45,” The Guardian Press, London, 1945.

Researched and written by Thomas Barden