‘I feel there was practically no realisation of what the development of mechanised forces really means; what labour is involved, and the amount of skill required both in the Services and out of them. That deficiency had to be made good, and the steps taken have, of course, been varied, but the Country should be grateful that there was in existence this available capacity for training through these Technical Colleges.’

- Rt. Hon. Ernest Bevin M.P., Minister of Labour, 1941.

A short while after the United Kingdom declared war, entertainment and education centres across the country were shut by the government. Cinemas were closed for fear of enemy bombing causing mass casualties, although most would open again within a month, and evacuation meant schools and colleges had closed, many being requisitioned to aid the war effort.[1] The South-West Essex Technical College was no exception and was ordered to close:

‘One evening in September 1939, a few days following the Declaration of War, the Principal and myself were pacing the College corridors, talking over the many rumours that were current in respect of the war use of our large and almost new building.’[2]

Two of the circulating rumours were if the College couldn’t remain open as a place of education it was to be used as either an emergency hospital or the headquarters of an Air Raid Precautions area control.[3] However, through great efforts by the Principal and Governors, the rumours were unfounded and no requisition powers were enacted. Within a few months ‘the energy and personal influence of the Principal [meant] education work recommenced, expanding…to proportions that tested the capacity of the building, making outside accommodation essential.’[2] The College re-opened on 7th October 1939 to 200 full-time and 113 part-time senior students.

After the evacuation of children and before the College re-opened to education the remaining staff, of which there were only ‘two or three dozen’, took immediate action to safeguard the building. The first action was to camouflage the workshop roofs which, being white in colour, were an easy bombing target or navigable landmark from the air. All the staff set to painting during the day while some of the younger staff took up residence at the College and established a night watch party.[3]

The decision to continue civilian education at the College during the war years was an important one. Courses were popular amongst the local population and helped to build many skills that were required during the war whether that be in factories, medical care, rationing or research & development.

During the first full academic year of the war the College was ‘one of very great activity’ with ‘the entire resources of the College [being] used in the prosecution of the war effort, both in training and production.’ The war put such a strain on space and resources that the unevacuated parts of the day schools were re-housed in the two former buildings located on Hoe Street and some rooms were used for teaching at the Sir George Monoux Grammar School.[4]

During the 1939-1940 session the College continued to offer evening classes, even during black-out conditions. This was continued into 1941, however, ‘owing to the change in the character of the war and the incidence of blitz conditions, it was deemed advisable to cancel all evening instruction.’[4] It was later arranged that those students who could only attend evening classes were provided a full programme of summer evening classes over a period of four to five months. These proved popular to students with 1,000 new enrolments received.

Dr Lowery highlighted the resilience and bravery of the students who attended classes ‘throughout the flying-bomb attacks during the summer of 1944.’[5] There was never a direct hit on the College building, but many bombs that were dropped locally did damage to the College. Air raid sirens and the noise of enemy planes would often send students and staff ducking in and out of the limited cover of their desks. In a summary of the College’s buildings, Dr Lowery reported:

‘The College workshops suffered considerable damage due to blast and many windows in the main building were broken and steel window frames buckled. A shelter at the rear of the building was demolished by a direct hit...a large bomb fell in the front grounds and brought down two trees and displaced some of our front steps.’[4]

One of the main issues with continuing education was ensuring people could access it; many people worked long hours in factories or had other wartime commitments such as the Home Guard, Red Cross or Air Raid Precautions. To cater for those who were unable to attend conventionally timed classes the College chose to run daytime courses at the weekend. The Sunday classes proved particularly controversial and Principal Lowery found himself corresponding with several local religious ministers who disapproved of the innovation. One Bishop’s objection was quoted in The Essex Chronicle during a debate between himself and Mr J. Hewett, Chairman of South-West Essex Regional Sub-Committee and College Governor:

‘I do not take objection to it on narrow, Sabbatarian grounds, but on the ground of the recognition of the special character of the Sunday in regard to human well-being.’

The debate seems to have ended abruptly after Mr W. J. Bennett stepped in to say:

‘All values have simply gone to pieces. For the moment everything is war, and there is nothing spiritual about war. So far as we can enable our youth to get the education necessary to fit them for their work, even if it is only turning out a sharper bayonet for the enemy, we must put up with it.’[6]

Even the Chief Inspector from the Board of Education telephoned on the opening day of classes to express his disapproval. The opposition from the Board of Education was, however, withdrawn upon the overwhelming evidence presented on how popular these courses had proved to students.[3] Once again, as in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the public had shown their fondness and thirst for technical education.

Mr W. R. Bray, writing in ‘The Country Should be Grateful’, described his first-hand experience of weekend classes:

‘I am a church-member and an official. For three or four war years I taught these students on Sunday mornings and then went to the afternoon service at my church. I know of several students who did the same. I would like to state here my considered opinion that the holding of these classes was a most useful education and social service carried out by the College for the community. Had the classes not been held, many students in the middle of their student life would have had their courses interrupted and would have found it impossible after the break to start their studies all over again. Many would have gone into the forces less well equipped than was actually the case. They were working all the week in factories, and apart from black-out, difficulties of evening travel, commitments in A.R.P., Civil defence and Home Guard, were too tired to do justice to their work at night. The week-end class was the only answer to the problem, and, as far as I know personally, in the case of those who wished to attend church, the fact of classes being held on Sunday morning proved no deterrent. The others would probably not have attended church anyway.’[3]

This sentiment is reinforced by Principal Lowery:

‘I feel sure that the great popularity of these [weekend] classes indicates the appreciation that students have for facilities for doing their studies in the day-time. Students who attend classes on Sunday mornings frequently tell me that they feel they are able to benefit more from College amenities.’[7]

The College’s weekend classes were incredibly successful. Over the period they ran they catered for 7,760 students. The peak was in the 1941-1942 academic year after which, due to ever-improving black-out capabilities, the weekend courses were slowly tapered off in favour of evening classes.

There were very few activities at the College that were completely separated from the war itself. Most courses were designed to train people for the civilian or military services or for work in factories producing arms and munitions. However, each year a number of students were given day release by their place of work to continue with their education. In total, 4,075 full-time and part-time students attended the College on release from their workplace between the 1938-1939 and 1945-1946 academic years.[3]

Keeping the College running during the war was not an easy task. Without re-opening the former schools on Hoe Street (and making use of other satellite locations) the College would not have been able to deliver education to so many. Equipment was another issue. When opened the College had been fitted with a large array of equipment but the combination of government requisition and the delivery of more specialised courses meant there often wasn’t enough to go around. Some assistance was provided by the Essex Education Committee along with local schools in the form of loaned machinery and tools.[4] Other equipment was located through staff contacts:

‘Of all the deals probably the most sensational was that in which a number of American lathes were purchased before even the boat in which they were being brought to England had docked. Mr. Cooper was at the dockside to meet them.’

Other sources throughout the war years included other colleges and universities, such as University of Manchester, the Manchester College of Technology and the Royal Society.[5]

In another bid to bring education to the community and to boost morale during air raids, Alderman Ross Wyld, Air Raid Precautions Officer, suggested the College could deliver lectures in air raid shelters. Two notable occasions were when Mr Astins, Chairman of Governors, gave a lecture on William Morris and Principal Lowery gave a lecture on astronomy. The lectures must have had impact as after the war a member of the Royal Air Force came to the College enquiring about astronomy courses.[3]

The College wasn’t all about teaching and learning during World War 2. The building was alive with groups, clubs and organisations created by both staff and students. The College’s social life spilled over into the local community who were invited to attend exhibitions and performances.

In an earlier article The College Amateur Operatic Society was mentioned. After its first performance of ‘Patience’ in April 1939 full-scale productions were interrupted due to the war, although several concerts were given to service personnel trained at the College.[8]

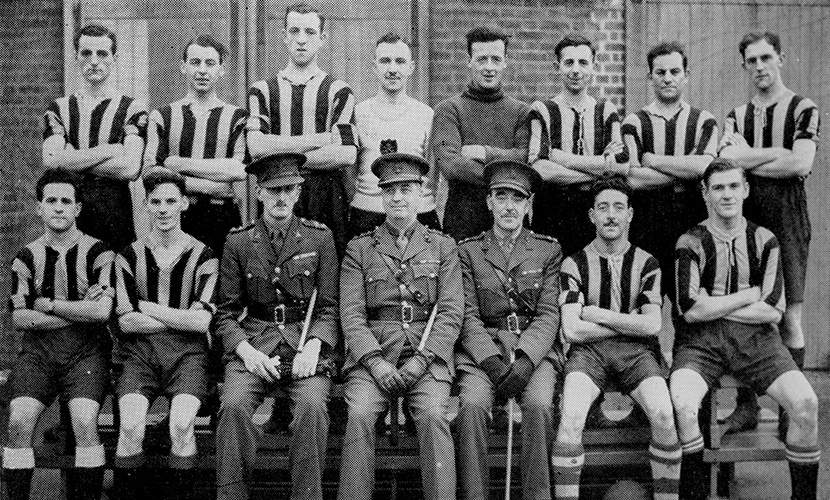

Showmanship did continue during the war with members of the armed forces putting on performances on the main stage. Mr W. R. Bray wrote:

‘There were many occasions on which the “enemy overhead” would have been mortified could he have seen how little attention was being paid to his efforts by the packed audience enthralled by the rollicking efforts of the boys on the stage.’[3]

The tone of one show can be summarised in the opening paragraph from the Walthamstow Guardian:

‘Bombardier Johnny Rice threw himself into his part with such abandon in the revue by H.M. forces, “Go To It”...on Saturday, that the final curtain, amid loud applause, found him with a cracked rib, sprained wrist and a bruised spine. Whether he sustained the whole of his “wounds” in the undress of his female impersonations, or in the gusto of his amazing male evolutions, is a moot point. The assurance that the show went away with a swing was apparently adequate compensation for his injuries.’[9]

Other events that occurred during the war years included the Service of Youth for young people, various exhibitions held by the Essex Art Club and an Exhibition of Models with all entries being made by staff and students. Principal Lowery sums up the ethos of college life by saying:

‘Perhaps the most important part of the educational influence of the College is to be found in the social contacts made through students attending the building for common interests. It seems to me that every effort should be made to make it possible for part-time students (who are usually making some sacrifice in order to attend classes) to be placed on the same level as full-time students in order that they may benefit from the social and cultural amenities of College life.’[7]

It must not be forgotten that this was a time of great uncertainty. Nobody knew what the outcome of the war would be, nor how long it would continue. To better understand the position those in education found themselves at the start of and during the war, and to highlight the brilliant way in which those people approached their jobs in extreme uncertainty of the outcome, we can look to the words of former Chief Inspector of Schools, London County Council, Dr F. H. Spencer:

‘Anyone who writes about Education Reconstruction is at once faced with difficulties. The first is that we are still engaged in the greatest and most destructive war this world has known. No one knows what will be left to reconstruct. We do not even know whether our chief tasks of rehabilitation will be these presented at home or abroad. We do not yet know with any finality what will be the economic position of Britain at the end of a war, which, if we are to have any reconstruction of our own willing, we must assume will end in complete victory for the nations allied against the Axis Powers. We may surmise – if we are bold we may prophesy – but we do not know.’[10]

References

Imperial War Museum, “How Children’s Lives Changed During the Second World War,” [Online]. Available: https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/how-childrens-lives-changed-during-the-second-world-war. [Accessed 17 07 2023].

P. Astins, “Foreword,” in The Country Should be Grateful - The War-time History of the South-West Essex Technical College and School of Art, The Walthamstow Press Ltd., 1947.

W. R. Bray, The Country Should be Grateful - The War-time History of the South-West Essex Technical College and School of Art, London: The Walthamstow Press Ltd, 1947.

H. Lowery, “South-West Essex Technical College and School of Art Annual Report Session 1940-41,” The Guardian Press, London, 1941.

H. Lowery, “South-West Essex Technical College and School of Art Annual Report Session 1943-44,” The Guardian Press, London, 1944.

The Essex Chronicle, “Bishop Deplores Sunday Work at Two Technical Colleges,” The Essex Chronicle, p. 3, 29 November 1940.

H. Lowery, “South-West Essex Technical College and School of Art Annual Report Session 1941-42,” The Guardian Press, London, 1942.

The First 70 Years of Song & Music: The College Amateur Society 1938-2008, London, 2008.

Walthamstow Guardian, “This Show Should Do the Rounds,” Walthamstow Guardian, 2 August 1940.

F. H. Spencer, “Education and Reconstruction,” in Education Handbook, Norwich, Jarrold & Sons Ltd., 1943, p. 5.

Researched and written by Thomas Barden