‘The Leyton Technical College is not disappearing from existence. Its staff, its boys and its evening students are merely being transferred to another building. I feel confident that, the experience, enthusiasm and success which has been Leyton’s will contribute to the success which we know will come to the South-West Essex Technical College.’

- R. W. Jukes, Acting Principal, Leyton Technical College, 1938.

The first year of teaching and learning at the South-West Essex Technical College would be one of delays, rush and a lingering threat of war. However, the activities of year one were good practice for the coming years of World War 2.

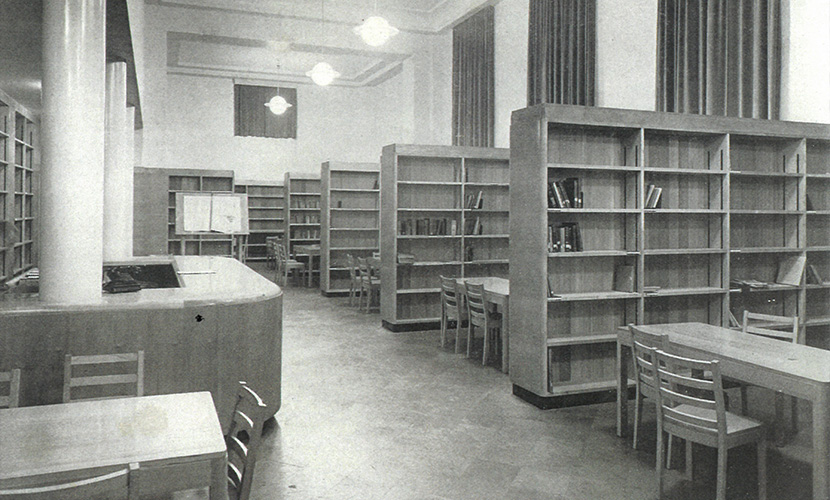

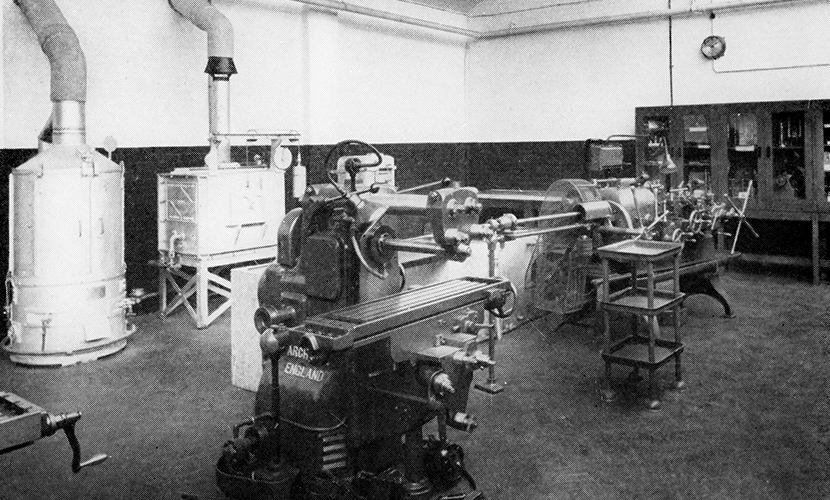

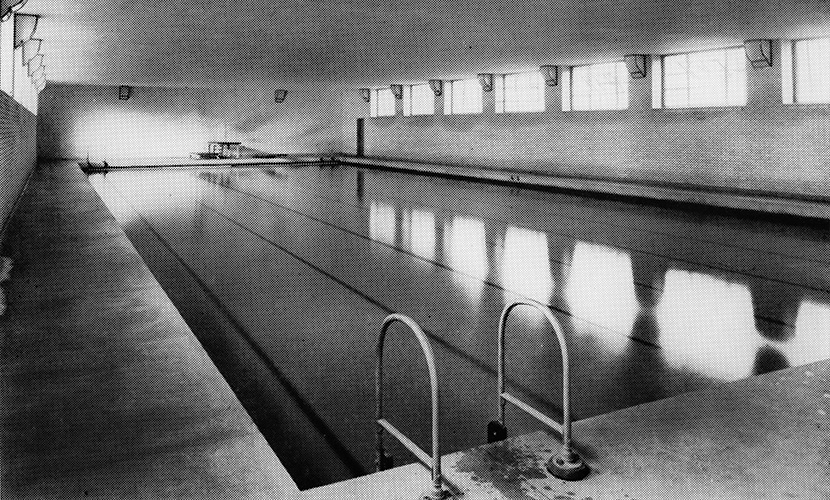

The immediate months preceding the first enrolment were of a frantic need to complete and fully furnish the building. Much of the large equipment to be delivered to the College was to come from the former Walthamstow and Leyton Colleges. This equipment had been in use up until the end of the summer term and so the task of packing down, moving and setting up in the new building would not have been easy considering the timeframe in which to complete. Another hindrance was in the workshops where much of the heavy equipment was to be placed. The building work had yet to be finalised and so it wasn’t until the end of August that equipment could begin to be transferred.[1]

In the first annual report to the College Governors, Principal Lowery highlighted another reason for the delays:

‘Difficulties in the labour market prevented many firms from giving punctual delivery of apparatus, the delay being most marked in the Engineering Department, though all departments experience some difficulty in this respect’.

Equipment would keep funnelling into the College throughout the year ‘so that students were not unduly handicapped in their courses’.

On Monday 19th September the College opened its doors for the first time with a week-long enrolment for evening students. At the end of a tiring, confusing and frantic week new records were set as the College enrolled 5,802 evening students, up 67% on the figures of the Walthamstow and Leyton colleges from the year before.[1]

During this period dark clouds were forming over Czechoslovakia leaving Europe in a state of unrest. On 15th September 1938 British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain flew to Germany to meet with German Chancellor Adolf Hitler to hear his demands regarding Czechoslovakia. Over the coming days there was a lot of political discussion between the nations of Britain, France, Italy, Russia and Germany; the Czech government, however, was kept in the dark.[2]

On 28th September Hitler invited Chamberlain, French Prime Minister Édouard Daladier and Italian Prime Minister Benito Mussolini to a meeting in Munich. The resulting Munich Agreement led to the annexation by Germany of the Czechoslovakian Sudetenland. Later, on 30th September Chamberlain returned to London and declared ‘peace for our time.’[2]

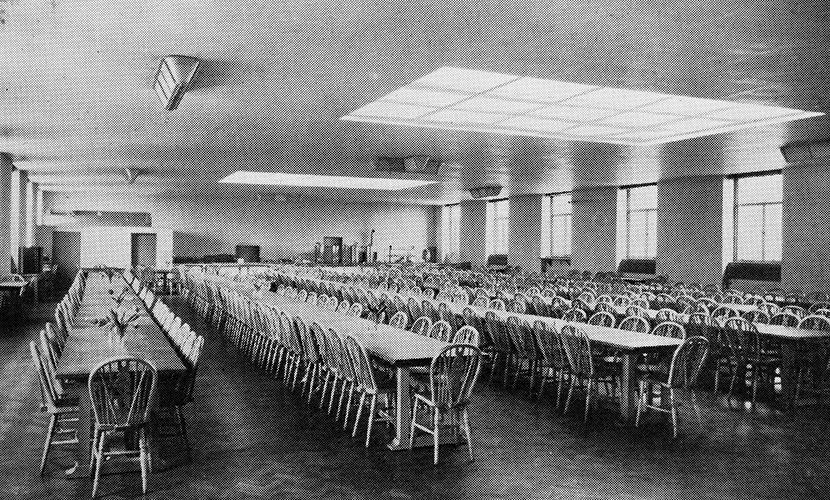

The experiences of the College’s first and hectic enrolment provided good practice for the weeks to come. On 24th September 1938, anticipating potential war, the government put in place evacuation procedures. As a result, on 26th September it was decided that teaching should be postponed for a week. All staff were called to duty and had the monumental task of sending letters of information; not only to the 900 day school children but to the 5,802 newly enrolled evening students. To help ease the chaotic situation, Principal Lowery and Head of the day school Dr Baron held a very cramped 2000 strong parents meeting in the Assembly Hall to explain the arrangements:

‘The uncertainties of the times, the crowded state of the hall and the purpose for which the meeting was called combined to make this first meeting of Principal and parents a memorable, if somewhat uncomfortable, occasion’.[1]

In his book, Mr W. R. Bray reflects upon a historical moment towards the end of enrolment week:

’The Governors met for the first time in their new board room….Although they [later] met in this room frequently…probably this first meeting, held while the hall and entrance were packed with would-be students, possessed for the Governors a thrill which was not to be repeated in later meetings, for were they not realising the coming to life of a dream, towards the attainment of which they had worked and given their energies for many years’.

Prime Minister Chamberlain’s return from Munich meant the dark clouds began to clear and the College finally opened on Monday 3rd October 1938. Despite the building being designed to hold a vast number of students the new intake meant the College building was fast running out of space. Teaching at the College was only active for two to three days before external accommodation needed to be found. This resulted in the old colleges at Walthamstow and Leyton reopening as satellite locations,[3] as well as making temporary use of any available space in the Sir George Monoux Grammar School. It doesn’t appear to be until 2017 that the College would fulfil its original purpose to bring all core teaching onto one site.

It wasn’t the start of the term that everyone was expecting. Building work was ongoing in the College’s corridors and in the outside spaces the landscapers were hard at work. To avoid the mud when moving around outside students and staff had to practice the art of ‘walking the plank’ and the first few months of lessons were disrupted by the sounds of heavy machinery.[1] There was, however, ‘a wonderful sense of cleanness and newness. Small boys were urged to keep their fingers off the walls [and] all day school pupils had to change into rubber soled slippers while in the building.’ All this work meant the Official Opening of the College was pushed back to 28th February 1939.

References

W. R. Bray, The Country Should be Grateful - The War-time History of the South-West Essex Technical College and School of Art, London: The Walthamstow Press Ltd, 1947.

W. S. Churchill, The Second World War: 1: The Gathering Storm, Fourteenth ed., The Reprint Society Ltd., 1961, pp. 234-266.

The Times, “Culture and Usefulness, Technical College at Walthamstow,” The Times, p. 13, 1 March 1939.

Researched and written by Thomas Barden