‘The events of the week had definitely put the College on the map. It might be praised, it might be attacked, but it could not now be ignored.’

- Mr W. R. Bray, 1947.

The South-West Essex Technical College and School of Art was officially opened by the Rt. Hon Herbrand Sackville, The Earl De La Warr, P.C., J.P.,.[1] Lord De La Warr, President of the Board of Education, was a great advocate for technical education institutions. He emphasised that where technical facilities had been opened they had filled up quickly with students. News coverage at the time suggests that authorities doubted him but, due to the vast numbers of enrolled students at the South-West Essex Technical College, Lord De La Warr should have been ‘glad of this example, for he will use it in many of his speeches when visiting other districts. He is convinced that there must be more enterprise in technical education to equip Britain to meet foreign competition’.[2] At the ceremony Lord De La Warr said:

‘[I am] convinced that in many cases, the inability to obtain or to keep employment between the ages of 18 and 30 was the direct result of what happened during the period between the ages of 14 and 18 years. Those who made use of such a college might sometimes fall into unemployment; but they need never become unemployable.’[3]

Others who attended the Official Opening included: Principal Harry Lowery; Chairman of Governors Mr Percy Astins; Rev. The Bishop of Colchester; Chairman of the Essex Education Committee Miss M. E. Tabor; and Chairman of the South-West Regional Sub-Committee Mr Joseph Hewett. All those who attended the Opening Ceremony were excited for the future of the College and of education; many had been instrumental in seeing the College built. Miss Tabor said she hoped that the progress in technical education in the second quarter of the 20th Century would be known to historians as a remarkable event.[3]

Lord De La Warr commented that he believed having education for all ages under one roof would increase the value of education. It would show that ‘education was not just a stage of life to be passed through and left behind, but a part of life itself; and that at no age is one so old or so knowledgeable that there is not plenty left to learn.’[3]

The College was originally built as a technical institute to help reverse the decline in skills and to benefit those stepping into the workplace. The range of courses available shows the College was starting to deliver just that. Principal Lowery, in his statement titled ‘Vocation and Leisure’, also looked towards the recreational activities of the College:

‘It is perhaps in the non-vocational and recreational activities of the College where the influence of modern educational ideas is seen to the best advantage. The necessity for recognising the true use of leisure has led to the conception of the “People’s University” and it is our desire that the College shall become one great educational and recreational community centre where men and women may meet in their leisure time for the purpose of engaging in matters of common interest, thereby securing the fullest opportunity for self-expression. Thus, classes in the art of reading and writing, international affairs, the drama, social and political theory, psychology and religion have been specially designed with this end in view.’[4]

At the heart of this recreational experience was the Students’ Union. The first Social Organiser was Mr T. Corkhill and ‘great strides were made on the social and cultural sides of student life.’[5] The Union helped to establish many activities such as badminton, table tennis, boxing, netball and a country and Morris dancing club with dances held on Saturdays in the College hall.[6] The first year also saw the founding of The College Amateur Operatic Society (CAOS). The Society was originally formed as an evening class and gave its first performance on Thursday 20th April 1939 making use of the College stage and hall.[7] The production was ‘Patience’ and had a cast of 32 women and 16 men. An amusing footnote in the original programme says, ‘Ladies are requested to remove their hats during the performance.’[8] The performance itself was met with great enthusiasm and was deemed a successful debut. The Walthamstow Guardian wrote in review:

‘This first performance in the College theatre can be described as an impressive start for an excellent company of players, who presented with charm, clarity and colour this popular Gilbert and Sullivan piece.’

It was also stated that if the play was a sign of musical treats to come, then ‘Walthamstow lovers of melody will make this delightful theatre their Mecca.’[9]

It is, however, the fate of anything new and progressive that it should come under criticism and attract controversy. The College was no exception. Miss Tabor mentioned the number of times she had been asked, ‘Why do you want such a great building? It is such a waste of money.’ Her response was to highlight that the building was not big enough as it had already overflowed to the old buildings and that ‘the amount spent here will be one of the best investments the country has ever made.’[3]

One aspect of college life that attracted attention was the introduction of the College nursery. The nursery provided specialist facilities where mothers could leave their children with a trained nurse while they went to class. One official at the College commented in the Daily Mirror:

‘We also have a handywoman’s class. That is useful for wives whose husbands are not very “handy” about the home.’[10]

After the Official Opening, The Daily Mirror ran another article about the College titled, ‘They Educate Wives, Mind Babies’, focusing again on the College nursery. The newspaper mentions:

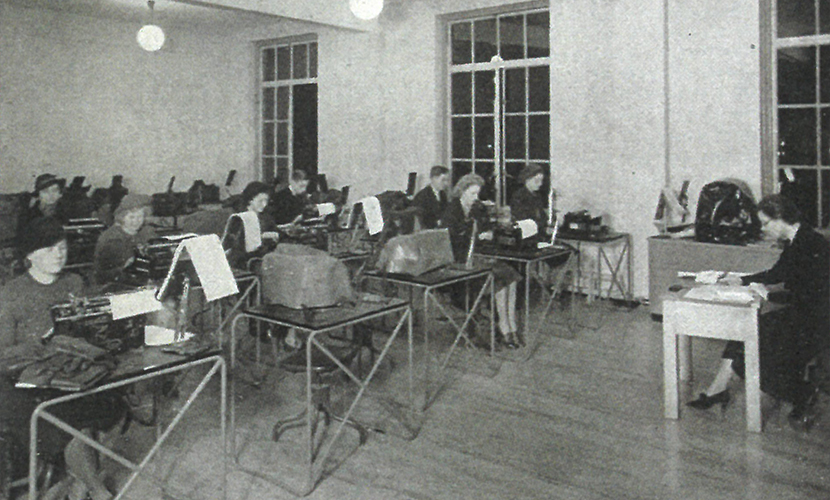

‘Young moderns, who can leave even tiny babies in the charge of a trained nurse, are giving the officials a surprise. Many of them insist on learning mechanics. “It’s amazing,” the Daily Mirror was told by an official, “I suppose these young women want to know how to repair a washing machine or a vacuum cleaner”.’[11]

Less than a year later, many women, some of whom may have been trained at the College, would be at the forefront of mechanics and engineering playing a vital role in maintaining the country’s industry during war time.

Despite scepticism and conservative views, the College was seen as an initial success:

‘The success of the College and the demands for its teaching are a credit to all concerned. It may well be a model for a substantial advance in education elsewhere.’[12]

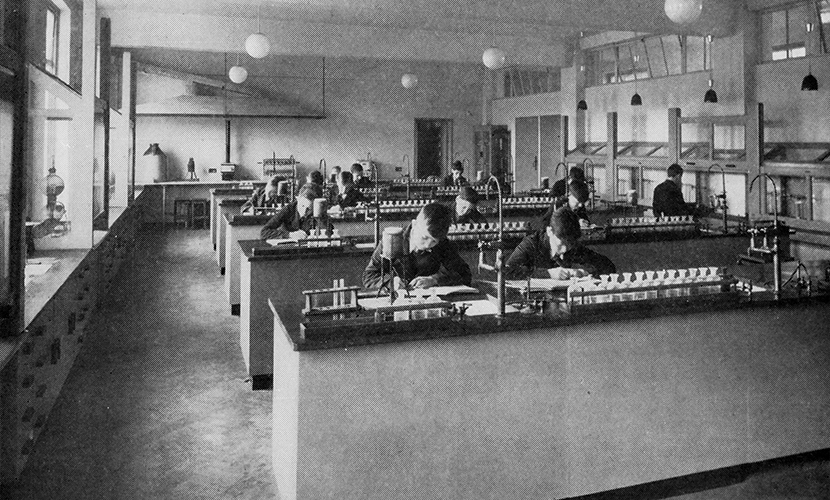

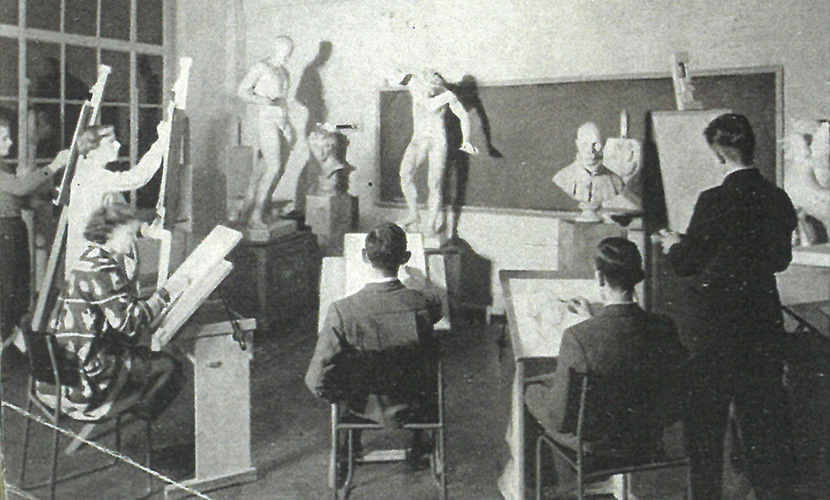

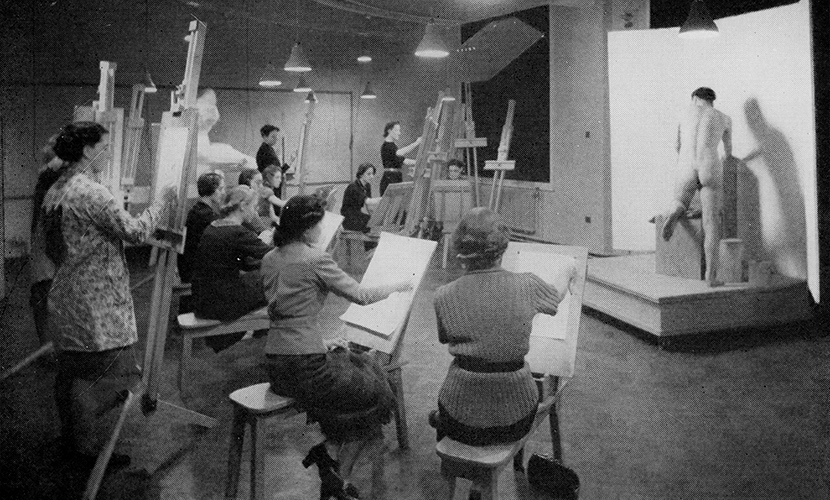

The Opening Ceremony was accompanied by an Exhibition of Work with demonstrations and exhibitions from many subject areas. Drawing, music, woodworking, physics, hydraulics and beekeeping to name a few meant there was something for every guest to enjoy as they explored the floors and corridors of the College. After touring the facilities guests were invited to the Principal’s Inaugural Lecture, which was followed by an Organ Recital in the College hall.

The Opening Ceremony was not the only success. On Saturday 4th March 1939 the College was opened to the public for the first Open Day. This was the first time the general public were able to enter the building and tour the facilities. Every room was able to be seen including the common room, swimming bath, laboratories (science and engineering), art rooms and library. Demonstrations were held across the College’s curriculum including arc welding, cabinet making, glassblowing, beekeeping, pottery and jewellery & silversmithing. A variety of exhibitions were also on display including the evolution of Walthamstow, historical maps, drawing & art and first year plumbing work.[13]

In the afternoon, and continuing into the evening, the College Hall came alive to performances by the orchestra, conducted by Mr L. J. Dyer, playing works by Wagner and Mozart among others. After the musical performances a gymnastics display was held followed by a one act play of ‘A Quaker Wooing’ by the Dramatic Society. The first floor also showed a series of films up until 8:30pm and when it was dark lantern talks on travel and transport were given.[13]

The Open Day turned out to be a major success and would have pushed the building to limits it hasn’t seen since. For years, the people of Walthamstow had watched this huge college being built, their curiosity building with it, until the doors were finally opened. The Open Day had 25,000 visitors who came by foot, bike, bus, train and car. Vehicles overflowed from the College’s grounds and were parked the length of Forest Road from Wood Street to the Bell.[5]

How much each individual saw at the event can only be guessed and how the floors survived under the weight of 25,000 marching pairs of feet is a testament to the build quality. In the end the day had a huge impact on the College. Lecturer and author Mr W. R. Bray said:

‘Those who stayed behind to put things straight felt that the events of the week had definitely put the College on the map. It might be praised, it might be attacked, but it could not now be ignored.’[5]

References

London Daily News, “”People’s University” for Leisure as well as Work,” London Daily News, p. 3, 01 March 1939.

Northants Evening Telegraph, “Education for Work,” Northants Evening Telegraph, p. 5, 28 February 1939.

The Essex Chronicle, “£220,000 College for 6000 Students,” The Essex Chronicle, p. 2, 03 March 1939.

Essex Education Committee, “Vocation and Leisure,” in Opening Ceremony of the South-West Essex Technical College and School of Art, Silver End, Witham, E. T. Hero & Co. Ltd., 1939.

W. R. Bray, The Country Should be Grateful - The War-time History of the South-West Essex Technical College and School of Art, London: The Walthamstow Press Ltd, 1947.

Waltham Forest College, Fiftieth Anniversary Waltham Forest College, London: Waltham Forest College, 1988.

The College Amateur Society, The First 70 Years of Song & Music: The College Amateur Society 1938-2008, London, 2008.

W. S. Gilbert & Arthur Sullivan, Writer, Patience or Bunthorne’s Bride. [Performance]. 1939.

K.D.J, “Technical College Operatic Society, Brilliant Debut with “Patience”,” The Walthamstow Guardian, 22 April 1939.

A Special Correspondent, “Babies Play While Mothers go to School,” The Daily Mirror, p. 5, 20 October 1938.

A Special Correspondent, “ They Educate Wives, Mind Babies,” The Daily Mirror, p. 17, 1 March 1939.

Nature, “The South-West Essex Technical College,” Nature, no. 145, pp. 775-776, 1940.

South-West Essex Technical College, “South-West Essex Technical College & School of Art Open Day,” in Programme of the Exhibition of Work, London, 1939.

Researched and written by Thomas Barden